Minority students attending Manchester schools are more likely to live in a poorer area and perform worse on standardized tests than their White classmates.

And those students have only a 1 in 20 chance of having a teacher who isn’t White.

Susan Kamola measures the inequities in other ways — for example, what happens when certain students leave Central High School during the school day.

“If all of us were going outside, someone would follow us,” said Kamola, who is Black. “If a White group of kids would leave the building, nobody in that circle would get questioned.”

“In general, I feel like the colored kids at our school just don’t get treated the same as the White kids,” the sophomore said.

Questions of race have taken on greater urgency as the school district grows more diverse and society calls for more equal treatment of people regardless of race. How Manchester deals with its diverse student body will help determine whether many students join the state’s workforce or move elsewhere.

The school district’s population of 12,400 students is split almost equally between Whites and minorities.

That means half the students see few faces among faculty that look like them.

Last year’s roster of 1,012 classroom teachers included 50 of color, according to district figures.

In the city’s 13 elementary schools, where 279 classroom teachers worked, there were five minority teachers.

“‘I’ve heard a lot of kids ask: Why don’t we have any other Black, Hispanic or Asian teachers?” said Namdi Williams, an instructor for My Turn, which helps prepare disadvantaged students in several districts, including Manchester, with academic and employment training.

“The more that they can see, the more hope they can have a chance,” said Williams, an African-American born in New Jersey whose parents are from Sierra Leone.

The pace of hiring

In June 2020, the city’s school board promised to hire more minority employees.

It unanimously approved a resolution stating the diversity of the district’s students would be reflected in its administration, staff and policies, sports and extracurricular activities.

But change has come slowly.

From July 1 through Nov. 29, the district hired 130 teachers. All but five were White, according to Tina Kim Philibotte, the district’s new chief equity officer.

“It is not acceptable at all, and at the same time, it is all too common in New Hampshire,” said the Korean-born Philibotte, who sometimes was the only minority teacher at her former job in Goffstown.

“It’s not that those who are applying aren’t qualified, but the reality is that if we are not creating accessible pathways to college for students of color, the hiring pool will have fewer candidates of color,” said Philibotte, who is working with Manchester Community College to expand opportunities for students of color to become educators.

“I don’t think that next year you’re going to have a bunch of teachers of color coming in,” she said.

Elementary school teachers, for example, are overwhelmingly White and female — both nationally and in Manchester, she said. All but 11 of the Manchester district’s 279 elementary teachers were White women.

“What you’ll often see are the girls will outperform the boys linguistically time and time and time again,” Philbotte said.

“There’s a correlation between the female educator and the female student, so when we start talking about a diverse teacher workforce, you could say that because the majority of our teachers ... are White, a lot of our students don’t have the opportunity to learn from somebody who has a common lived experience,” she said.

Disparity throughout

Carlos Gonzalez, the only person of color on the Manchester school board, said “not much” has happened since that June 2020 resolution, which preceded his appointment to the Ward 12 seat.

Gonzalez hopes the teacher workforce will come to more closely reflect the student body.

“Try to get the best pool of diversity into the school system,” said Gonzalez, who was born in the Dominican Republic and identifies as Black. “That will help out a lot with the diverse population, particularly the new generation coming up.”

People looking for minority principals and guidance counselors would be hard-pressed to find them. One of 23 principals and one of 54 guidance counselors were non-White, according to district figures from October 2020.

Others don’t see the need to diversify the workforce, including Rep. Richard Littlefield, R-Laconia, who backed a controversial bill that would have banned teaching, for instance, that the state of New Hampshire or the United States is racist or sexist.

“Their success is going to do more for them in their life than having teachers that have the same skin colors,” said Littlefield, who is White and has three children in Lakes Region public schools. “I don’t believe that’s necessary for any child to learn and be successful.”

Decades ago, Manchester was home to more residents of Greek and French-Canadian descent, with various nationalities operating their own social clubs, said Alderman at Large Joe Kelly Levasseur.

“There’s always a struggle for power and authority and positions of wealth by all people,” said Levasseur, who is White.

“The women have pushed through the barrier in Manchester,” Levasseur said, with Mayor Joyce Craig and other women serving on various boards.

“We don’t look at people as Greek, French, Italian and Polish. Now, we look at people by their color, which I think is an unfortunate thing,” Levasseur said. “I think the breakthroughs in racial barriers are coming.”

Race and income

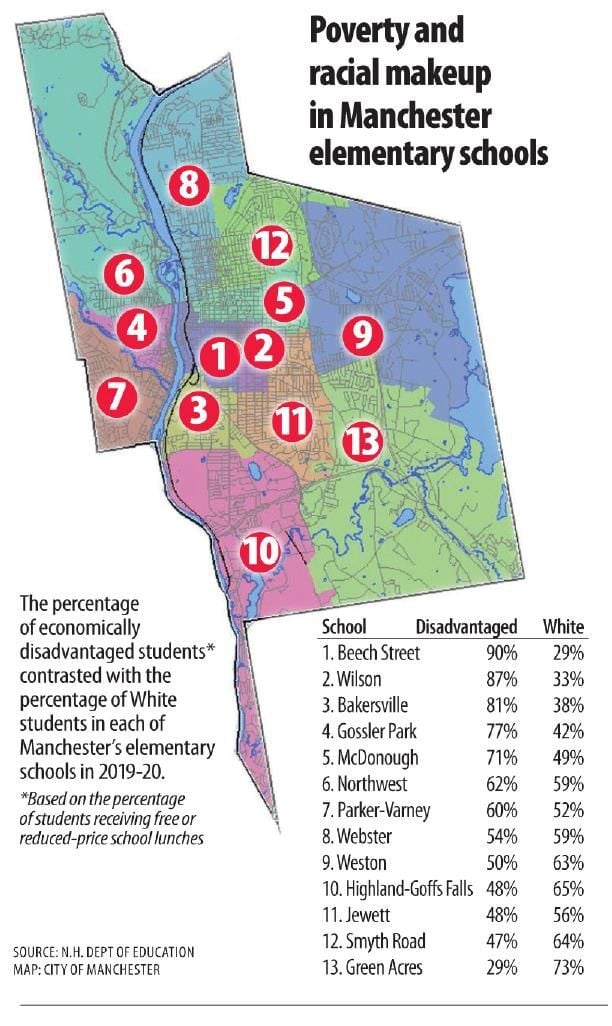

The least White schools in Manchester were found to be the most economically disadvantaged in a New Hampshire Union Leader analysis of state education data for the 2019-20 school year.

The five schools with the highest percentage of minority students also had the greatest percentage of poor students.

Topping the list was Beech Street School, where 71% of students were of color and more than 90% were deemed economically disadvantaged, based on eligibility for free or reduced lunches, according to the state education website.

Wilson, Bakersville, Gossler Park and McDonough schools rounded out the top five.

On the flip side, Green Acres, with the highest percentage of White students at 73.4%, had the lowest percentage of economically disadvantaged students.

“Those trends are going to line right up with …. health outcomes,” Philibotte said. “They’re going to line up also with low income-earning families, and it’s going to line up around race.”

Many of these issues are facing the state and nation, she said.

So who is responsible for making schools more equal?

“Every single one of us,” she said.

Emerald Anderson-Ford, chief diversity officer at the YWCA New Hampshire, believes some families have migrated to other areas.

“As soon as immigrant and refugee populations showed up, let’s say at Beech Street (School), and other folks of color ... here located in these areas, what we’ve seen is our White counterparts move to a different part (of the city) taking their influence and economic privilege with them,” said Anderson-Ford, who’s a Black American.

Means vs. opportunity

“I think the opportunities are equal among all students,” said Anderson-Ford’s husband, Damond Ford, who works for GearUp Manchester, a federal program designed to increase the number of low-income students preparing for career options and for entering college.

“The resources are there,” but not everyone knows about them, he said.

“I think that’s where the disconnect is,” said Ford, who is Black.

“I think they get the same opportunities as everyone who wants to work for it,” said Levasseur, who grew up in Manchester. “It’s whether or not you want to go get them.”

During a discussion with Central High students at My Turn’s office, Executive Director Allison Joseph explained the value of networking, a concept many students weren’t familiar with.

“It’s all about who you know when it comes to getting a good-paying job and making those types of connections or being able to capitalize on those opportunities that maybe haven’t been published yet,” Joseph, who is White, told the students.

Anderson-Ford later said that shows many students of color don’t have access to decision-makers.

“The idea that it’s a new concept also speaks to the privilege of it all,” she said.

What test scores show

Students in certain grades were tested in math, science and English language arts this school year. Results are represented as the percentage of students proficient in each subject and can be broken down by race.

By that metric, White students scored at least twice as well as Black or Hispanic students in each of those subjects, according to results on the state Department of Education website.

Philibotte acknowledged the disparity.

“Test scores are significantly lower” for Black and Hispanic students compared to White students, Philibotte said.

Other measures of economic disparity are harder to track. The Union Leader requested a racial breakdown of city welfare clients, but that office doesn’t collect such information.

“I realize that this is a piece of data which is getting more attention in recent years and when we next update our application we will likely include this question,” Manchester Welfare Commissioner Charleen Michaud said in an email.

A role model

Jason Bonilla, a first-generation Salvadoran-American, is expected to be nominated this week to fill a school board vacancy in Ward 5.

“It’s time for younger individuals of color to take the stand and to have these stories and to have our voices heard,” said Bonilla, 30. “I want New Hampshire to hear my voice as well, and I want our younger generation to hear me, so that they can see that this is possible.”

Before the district hires more teachers of color, it needs to have “tough conversations on why students of color don’t have the same opportunities and access” as White students do, said Bonilla, who co-founded New Hampshire Millennials of Color and recruited young people of color for City Year to serve as peer mentors in Manchester.

“You just can’t put us in a place and then expect everything to just go smoothly without acknowledging my humanity, acknowledging our history and being cognizant of the racial tensions that we have in this country,” he said.

The school board’s Gonzalez said he doesn’t like to view the world through a racial lens.

“It’s very unfortunate we’re in the year 2021, and we’re still struggling with this division that is basically in this society,” he said.